Some think renaming ‘disabled parking’ or ‘disabled toilets’ to include ‘accessible’ fixes everything…

By Maria

Disability’ is something imposed on top of a person’s impairments by the way they are unnecessarily isolated and excluded from full participation in society.

Disability’ arouses pity and pity peddling. ‘Disability’ arouses hero inspiration for doing normal stuff. ‘Disability’ arouses invasive inquisitiveness. ‘Disability’ suggests tragedy. ‘Disability’ stands for dispossession and misery. ‘Disability’ confirms one-dimensional. ‘Disability’ purports need fixing. ‘Disability’ is a plot device. ‘Disability’ is failure. ‘Disability’ means different treatment. ‘Disability’ confuses merit and diversity. ‘Disability’ induces protective activism. ‘Disability’ is a research dream. ‘Disability’ is visible. ‘Disability’ means confined. ‘Disability’ is a government welfare service provision policy. ‘Disability’ equals intrinsically vulnerable in status. ‘Disability’ means low expectations. ‘Disability’ equals trouble. ‘Disability’ is a bad thing. ‘Disability’ insinuates being poor. ‘Disability’ piles on loss of function. ‘Disability’ includes chronic and age-related illness. ‘Disability’ toots less value. ‘Disability’ dents pride. ‘Disability’ is a deep blow to one’s sense of identity. ‘Disability’ gives sought out parking spots. ‘Disability’ is taught as a discipline in university lectures. ‘Disability’ does not allow romantic engagement.

In 1970 Disabled in Action was formed by a group that included many Jenedians. The group organised protests, traffic blockades, a four week sit-in. The door had opened and the Jenedians walked through it. For decades, Jenedians continued to participate in activism and advocacy that led to the passing of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990.

Maybe, 1976 was the starting point for the social model after the publication of The Fundamental Principles of Disability by the Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS). In the UPIAS view it is society which disables physically impaired people.

Wherever it started the ‘social’ model of ‘disability’ is an activist/campaigner model and not a collective humanitarian model.

The ‘social’ model of ‘disability’ has been developed by self-advocating ‘disabled’ people who say their problems lie in the puddle of barriers society imposes upon them. Some via infrastructure but more so by ‘ableism’, that is the attitude all society has to their ‘we’ must have to be equal and independent mandate.

For example, “The problem is not that I cannot get into a lecture theatre, the problem is that the lecture theatre is not accessible to me…” Sheesh! The reformatting of a sentence does not change that the person could not get into a room they need to get into.

Another example “We have to insist that our personal troubles are public issues that need to be resolved…” Professor Mike Oliver, a tetraplegic due to breaking his neck in a diving accident at age 19 years, British sociologist, and disability rights advocate.

The Professor’s acclaimed publications are reported to have firmly established ‘disability’ as an academic field and laid the foundations of the ‘social’ model of ‘disability’. A model that stipulates the difficulties of living with a disability are not caused by the disability itself but are due to society’s failure to adapt to the needs of ‘disabled people’.

The Professor’s assertion is blatantly wrong! The social model of disability’s academic answer is to create an accessible ‘disability’ fantasy fairyland! A society rescue plan of ‘the poor things’ based on fluff and puff… and pitiful emotional blackmail to change laws not attitudes and knowledge.

The Professor convinced ‘disabled people’ under his influence to view the discrimination that they faced daily as a matter of human rights rather than as a personal tragedy from a medical problem.

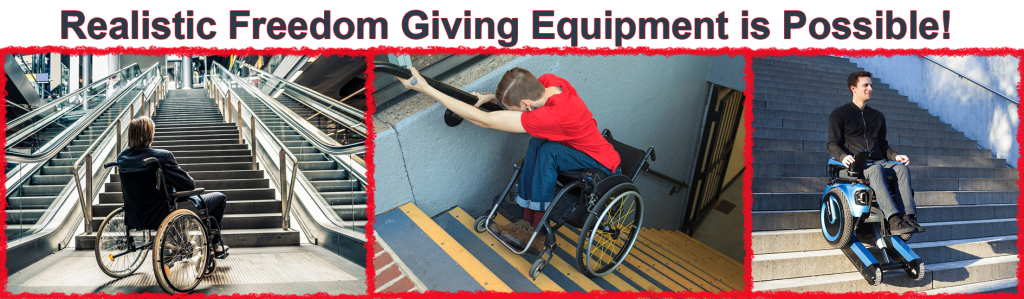

‘Social’ model says for Professor Oliver to be an equal in society built for the ‘abled’ it is the buildings fault. All steps should be replaced with ramps or elevators, all halls and doorways in every public and residential building should be wide as this will fix the wheelchair users access to society. The professor believed the individual is regarded as ‘disabled’ by society by the built environment and not by their own impairment.

The built environment is only one small part of the real barriers.

Why is it not possible that every healthy person in a prosperous society, who cannot stand up and walk, have a compact wheelchair that goes up and down stairs? As a starting point and then other technologies that allows, figuratively speaking, the opening of closed doors? Freedom giving equipment accommodating the independence restrictions imposed by the individual’s body damage.

The real problem is it does not matter how you say it, who you want to blame, until someone points out access to the building, for some who require the use of it, is not adequate for what the building offers in service to the community nothing changes.

Equal opportunity of access to the lecture theatre for people using certain aids to assist them enter has not been previously considered, therefore, dealt with.

For some the sold ‘social role’ is a treasured gift that recognises and sustains inequity while seeking to heal relationships in a culture that appears willing to help. New ways of getting ‘recognition’ as ‘disabled’ by society are being found all the time.

The medical model of ‘disability’ is said to look at what is ‘wrong’ with a person and not what a person needs, so it is viewed by the ‘social’ model of ‘disability’ supporters as paternalistic, uncaring, treatment and cure focused, and overprotective.

Ultimately, using either the social or medical model ‘disability’ is seen as something that must be explained, understood, and ultimately overcome, as the most human desirable experience is based on living in an unmistakably normal body environment. ‘Disability’ a continual fight to win, fight to stay alive, a fight to live in this world.

Today, it is considered offensive, insensitive to say, ‘disabled people’. The genteel language is stated to be ‘people with disabilities’ because ‘disabled people are people first’ or ‘people come first’.

What codswallop!

Is the two-word phrase really any different from the three-word societal identification? Does it stop any such person from feeling they have to pretend that they are just like everyone else, that they do not need any ‘special treatment’, or that their life experience does not mean anything in particular.

Do normal people use a toilet that is not flushing properly or use a parking space that has defects? Some think by renaming ‘disabled parking’ or ‘disabled toilets’ to accessible parking or accessible toilets changes everything… well it does not.

The word ‘cripple’ has been used in the English language since 950 AD. A word used to describe a person or animal who through injury or illness is no longer able to use one or more limbs. Yet, since the 1970’s the word has been turned into a negative slur and ‘person with disability’ or ‘disabled people’ became the right words to use.

Mental retardation simply means someone has a lower IQ than the average man. Yet advocates for individuals with ‘intellectual disability’ have self-righteously asserted to the United States government that the term ‘mental retardation’ has negative connotations, is offensive to some people, and can result in misunderstandings about the nature of the disorder and those who have it. The result is the United States government has legislated to change ‘mental retardation’ references in legislation to ‘intellectual disability’.

‘Modern respectable language’ does not change the IQ or circumstances of a person who has a medical term applied to their brain condition. Public awareness is diminished because ‘intellectual disability’ as a term is broad, vague, lazy and hazy, and does not pay respect to the consequence of living in society with the medical diagnosis of mental retardation.

The risk of loss of community support for mentally retarded people becomes an authentic realism.

Unlike ‘disabled’, cripple and mentally retarded do not have an opposite pole. No one is called an ‘uncrippled’ or an ‘able cripple’ or ‘mentally able’. The words cripple and mental retardation relate to body conditions and not a personal oddity.

‘Disabled’ has an opposite and that is abled. Disabled means not having ability to do, whereby, abled means having a full range of ability to do.

Able means having the power, skill, means, or opportunity to do something. ‘Disable’ means to put out of action, weaken or destroy the capability of, to make ineffective or inoperative.

It is time the language changed again. It is time models where thrown in the bin. It is time human rights are acknowledged as Cadbury chocolate… wouldn’t it be nice if…

Identity is a grouping of attributes, qualities and values that define how we view ourselves, and feasibly how we think other people see us.

The ‘social’ model takes away individual identity, and the loss of that identity can result in harmful psychological trauma. Such loss can result in increased levels of indiscriminate and social anxiety, depression, sadness, low self-esteem, a loss of self-confidence, isolation, chronic loneliness, all of this threatens one’s ability to connect with other people.

If one loses their identity and sense of self, they are likely to seek their sense of self-worth from others. Suddenly how others view them becomes particularly important, as their sense of value and self-worth, their feelings of confidence, are dependent on external factors such as physical appearance, success, status, money, and celebrity status.

Reassurance and praise from others to feel OK about themselves becomes a necessity. Yet, in truth, one’s emotional well-being depends on how one feels about oneself.

The ‘social’ model takes away one’s sense of self. It tells the ‘disabled’ in society to put on an act, a facade, a mask and deny their impairment as part of who they are and what they as an individual need. That is why so many people with ‘disability’ refer to themselves as a ‘crip’ or ‘gimp’.

‘Disabled’ is a cruel word that puts down, in a humiliating way, a group of people who feel anything other than powerless to achieve immense happiness and success in their life.

‘Disabled’ suggests the whole person is not ‘able’ and places the load of being unable to join in, or do things, in ‘normal living’ on their shoulders. Toxic shame, the lens through which much self-evaluation is viewed, is felt because of a surreptitious transference of societal non-disabled guilt.

Where does ‘disability’ sit on the Health Couch? Is it a disease (a specific deviation from a biological norm), a sickness (a social acknowledgement of a disease), an illness (a personal incidence of poor health or wellness)? Or is it something else?

The supreme, poignant abuse and violation of ‘people with disability’ is ‘disability’ being preserved and endorsed in a cluster of words… disease, sickness, illness.

Being unwell, ailing… not being in a healthy condition… people either recover or die when they have a disease, a sickness, or illness. However, being ‘unable’ leads to social justification of toxic shame because ‘disability’ does not cause death and most often has no recovery path.

People living with permanent body damage support should never be confused with medical or health support. Yet everywhere around our world via the United Nations convention it is becoming more so.

“The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and its Optional Protocol (A/RES/61/106) was adopted on 13 December 2006 at the United Nations Headquarters in New York and was opened for signature on 30 March 2007. There were 82 signatories to the Convention, 44 signatories to the Optional Protocol, and 1 ratification of the Convention. This is the highest number of signatories in history to a UN Convention on its opening day. It is the first comprehensive human rights treaty of the 21st century and is the first human rights convention to be open for signature by regional integration organizations. The Convention entered into force on 3 May 2008.

The Convention follows decades of work by the United Nations to change attitudes and approaches to persons with disabilities. It takes to a new height the movement from viewing persons with disabilities as “objects” of charity, medical treatment and social protection towards viewing persons with disabilities as “subjects” with rights, who are capable of claiming those rights and making decisions for their lives based on their free and informed consent as well as being active members of society.

The Convention is intended as a human rights instrument with an explicit, social development dimension. It adopts a broad categorization of persons with disabilities and reaffirms that all persons with all types of disabilities must enjoy all human rights and fundamental freedoms. It clarifies and qualifies how all categories of rights apply to persons with disabilities and identifies areas where adaptations have to be made for persons with disabilities to effectively exercise their rights and areas where their rights have been violated, and where protection of rights must be reinforced.

The Convention was negotiated during eight sessions of an Ad Hoc Committee of the General Assembly from 2002 to 2006, making it the fastest negotiated human rights treaty.” UN website

“The purpose of the present Convention is to promote, protect and ensure the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms by all persons with disabilities, and to promote respect for their inherent dignity.

Persons with disabilities include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which, in interaction with various barriers, may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.” United Nation Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities Article 1.

People with ‘disability’ being discussed as something, viewed before the United Nations convention as “objects”, to after the convention being viewed as “subjects”.

Dictionary definition of “object” is ‘a person or thing to which a specified action or feeling is directed’ and “subject” is ‘a person or thing that is being discussed, described, or dealt with’.

Hmm! An object of the narrative or a subject of the narrative.

In line with the United Nations convention ‘theme’ the Australian Commonwealth Disability Discrimination Act, 1992 currently defines ‘disability’ as:

disability, in relation to a person, means:

(a) total or partial loss of the person’s bodily or mental functions; or

(b) total or partial loss of a part of the body; or

(c) the presence in the body of organisms causing disease or illness; or

(d) the presence in the body of organisms capable of causing disease or illness; or

(e) the malfunction, malformation, or disfigurement of a part of the person’s body; or

(f) a disorder or malfunction that results in the person learning differently from a person without the disorder or malfunction; or

(g) a disorder, illness or disease that affects a person’s thought processes, perception of reality, emotions or judgment or that results in disturbed behaviour;

and includes a disability that:

(h) presently exists; or

(i) previously existed but no longer exists; or

(j) may exist in the future (including because of a genetic predisposition to that disability); or

(k) is imputed to a person.

To avoid doubt, a disability that is otherwise covered by this definition includes behaviour that is a symptom or manifestation of the disability.

A ‘subject’ who has no mental capacity to make decisions for themselves cannot under any circumstances change what is happening to them from a care or welfare position. It is impossible for them to engage in any concept of identifying as or living as a ‘full and effective participant in society’.

A ‘subject’ who is unable to communicate with their outside world cannot under any circumstances make decisions or command a certain type of treatment for themselves. It is impossible for them to engage in any concept of identifying as or living as a ‘full and effective participant in society’.

Making an accurate, honest statement about these people’s mental and physical condition without fearing push back from ‘the compassionates’ is these people’s road to dignity starting point.