A local native Arrernte artist has explained that ‘dot painting’ is about cultural law and watercolour paintings were about culture of country followed in the dweller’s area.

In a government settlement town of Papunya in Australia’s Western Desert, in the very wet year of 1971 ‘Aboriginal Race’ Dot painting originated. 52 years ago. This art style has no ancient cultural heritage no matter how many people try to dispute this romantic truth.

Papunya Tula is a small hill to the north of the town and a site of honey ant dreaming. It is also the name of the Company set up by whitefella, Geoffrey Bardon, with a government arts and crafts grant. A government grant given to assist the local natives manage the process and collect and distribute the money they received from selling their artwork.

Papunya was founded as a local native government settlement in 1957. A bore was drilled, and basic housing was built by the government to provide a place for the rising numbers of local natives in existing missions and reserves to move to. Access to clean running water, regular food supplies, clothes, bedding, basic housing and motor cars made them mindbogglingly prosperous compared to their previous nomadic hunter gather lifestyle.

Many of the nomadic local natives at that time were born at undisclosed locations in an unknown year. The hunter gatherer lifestyle found these people living an exceedingly perilous existence in a tremendously harsh desert environment. These people took voluntarily refuge offered by the government to escape from the burdens of life living the old way in the Western Desert.

Lutherans from Hermannsburg also came. The notion that this settlement was set up for the convenience of government to ‘subjugate’ and ‘assimilate’ these local natives is pure nonsense.

About 1400 local natives from different desert clans, including Pintupi, Luritja, Walpiri, Arrernte, and Anmatyerre at the time were being introduced into the emerging English speaking Australian society’s way of life. An immense barrier was the number and variety of local native languages spoken. A volatile mix making a volatile town.

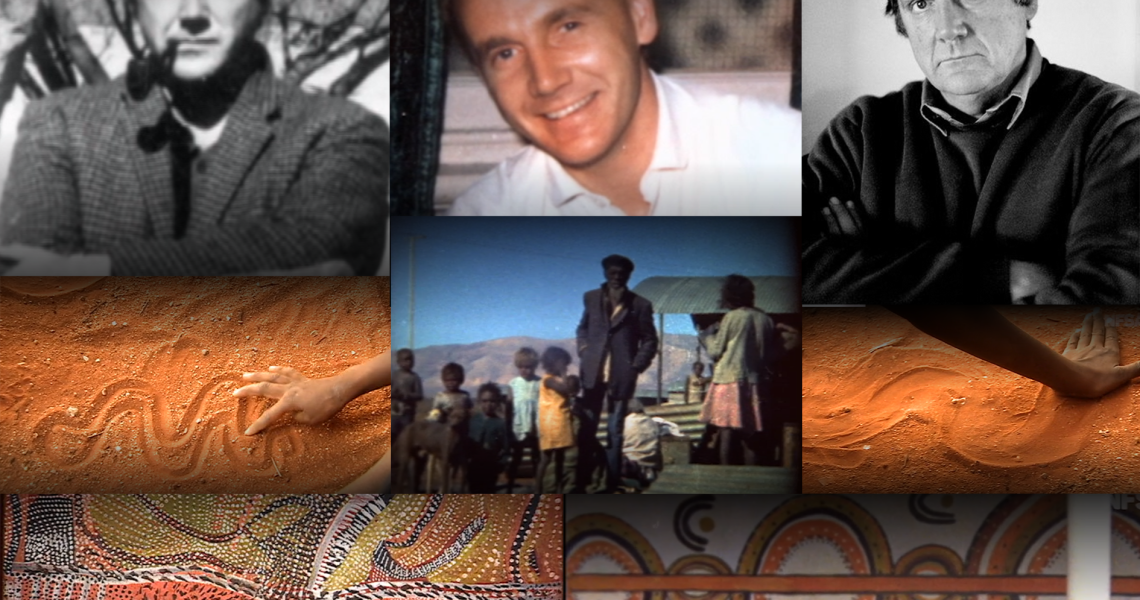

Geoffrey Bardon was born of a pure whitefella genealogy in Randwick, Sydney in 1940. He studied law at a Sydney university and before graduating he changed career direction and obtained an art education degree from Sydney National Art School in 1965. After graduating as an art teacher he worked in country New South Wales and Darwin. He had a desire to make a difference, to make films and produce high quality still photographs. He stated that he was not a businessman, teaching and art were his specialty.

In February 1971, Geoffrey Bardon a 30 year old blue eyed, tall man with unruly blond hair and an open mind, travelled along a 250 kilometre highway and crude red dirt road northwest from Alice Springs to the troubled government settlement at Papunya to take up the position of art teacher. With his rabbit trap and tool kit he was confident he could make the world his own. In his mind he was being paid like a millionaire to teach children in rags art.

Geoffrey Bardon was a sensitive, respectful, and kind man who took his 16 mm film camera and other expensive photographic equipment to Papunya with him. He was an artist and described Papunya as a hidden place unknown on maps and considered by officials as a problem place, a community in distress, struggling for survival with disruption, confusion, and despair.

Oppressed Papunya was a place of emotional loss and waste. Geoffrey Bardon observed that the settlement staff consisted of many men displaying little compassion and clearly not interested in helping the settlement residents.

Sometimes odd things would happen which he could see confused the residents. Like he watched ‘aboriginal’ men watering plants without an understanding of why and others chopping firewood then stacking it on the veranda of the settlement manager’s abode to provide wood for European fires of the winter time.

The chronic problem in the settlement Geoffrey Bardon saw was there was nothing much to do and people were bored.

While teaching he observed children sitting in the sand drawing shapes and making tracks of dogs, and kangaroo with their knuckles and fingers. He noticed whilst the local native men were telling stories they would draw symbols and animal tracks in the sand. An art style realized before his eyes.

Within 18 months of his arrival Geoffrey Bardon’s influence triggered the Western Desert art movement, said to be one of the greatest innovations in twentieth century art.

With his whole class in tow they would go out for bush walks or drive, often travelling over 100 miles around the local countryside in his powder blue Volkswagen combi van. Learning, having fun, and playing in and around the dams near iconic outback windmills with sound of metal creaking as the blades, ever so slowly, rotated around and around.

After work, out at the airstrip, Geoffrey Bardon would allow the local native men to learn to drive his combi van. Filming their efforts kangaroo hopping and juddering across the tarmac. He offered friendship and he was respected.

Geoffrey Bardon felt that it was a waste of time for the local native children to draw the whitefella cowboys and Indians when they had a drawing culture all of their own. He recognised a spiritual relationship drawn from the native children’s imagination to their dreaming. He would get the children to draw something like a kangaroo then he would measure it like he did on a test. If he didn’t like the art he he would throw it in the bin and ask for a second attempt. If he didn’t like the second attempt he would throw it in the bin and ask his student for more. When the child drew a double kangaroo he liked it and the child was rewarded. Drawing on the blackboard he taught the children art patterns to incorporate in their drawings and as a result was called Mr Patterns.

Geoffrey Bardon encouraged his students to paint their traditional designs using whitefella materials. Six outdoor murals were painted on the school walls at Papunya in 1971. The first realist style mural was of a family group sitting in the foreground of Haasts Bluff. This mural was painted over. The teacher inspired the children to create a mural based on traditional dreaming. The murals sparked astonishing interest in the community.

The elder men said the children did not know the full meaning of the motifs they were drawing. They said secret/sacred elements had to be suppressed, omitted or disguised within the painting. Soon many of the ‘elder’ men were involved in planning and painting the other five murals. The honey ant mural was a legitimate blackfella cultural icon. A masterpiece in Western Desert art. The local native men would sit on the ground near the mural and sing the honey ant song. The Honey Ant mural was completed with terrific enthusiasm with no prompting or persuading required.

Today only pictures of the murals remain as the originals were painted over in 1974 during routine clean-up maintenance of the government school buildings.

The settlement residents were encouraged to paint their stories onto canvas, on boards, discarded tiles, building remnants, cardboard, fence palings and many other things lying around. Up to 30 men gathered daily in a ‘fever of painting’ to paint on other things as well. In the active tidy paint room floor tiles, sawed up tables, scraps of skirting boards, house paint, shoe polish were utilised.

Geoffrey Bardon marvelled at the beautiful world of poetic intensity that was in these local native men’s mind. Water dreaming, bush tucker dreaming, wild tomato story, grasshopper story, travelling story, women’s story, wallaby dreaming a universe being created before his eyes.

The original paintings done with the touch of fingers rendered the spiritual nexus of the artists dreaming. He thought the dreamtime story of what causes rain was very poetic. In the dreamtime the power of a man’s voice that sings in a cave at night with a fire induces the rain. A lovely idea, not rational, and a very innocent thought.

Then the artworks were included for sale in the whitefella marketplaces, and the local natives earned whitefella money for the artwork they produced. This is an example of an inclusive society.

Geoffrey Bardon documented everything the artists did. He traced the designs and wrote names on the local native’s work to keep a record of who did what. He took two photos and recorded the story of every painting. During 1971 he travelled to Alice Springs and sold the dot paintings to bring home to the Western Desert local native artists $1300- to $1,500- per fortnight. Some artists were very well paid for their painting and the artists echoed this was the first time ‘whitefella society’ had placed any kind of value on anything they had ever done.

The artists enjoyed painting and it kept them so busy it disrupted the system of work in the settlement. The manager of community said, ‘my fella’s should be chopping wood not painting with Geoff, the firewood was not on the veranda when it should have been’. The conflict created a mess. Something that was gratifying became a political battle.

Geoffrey Bardon’s efforts were sabotaged. People tried to exploit the local native artists by offering cheap prices for their work to then sell them for higher profit, so the bureaucratic native administrators came to the rescue. This caused the regular fortnightly payments to the settlement residents to be delayed for six weeks.

All the artists who did such good work were not paid the full sale price or paid in a timely manner. The artists were charged costs out of the sell price for the paint and other equipment they used. There were questions about the gravy train material costs and administration of the artists money. The painters did not like not being paid properly for what was irrefutably theirs to sell and expressed anger at the betrayal shown by the whitefella authorities. At a meeting in mid-1972 the painters sat on the ground and chanted ‘money, money, money’. This hurt Geoffrey Bardon deeply as he saw the local natives who were theoretically being raised up and restored again were being stepped on and crushed back into the earth by ‘Aboriginal Race’ bureaucracy.

No regular pay made life very difficult for these artists, and they stopped producing artwork until they got their money. The pressure mounted on Geoffrey Bardon who had no friends to fall back on in the government blackfella administrate world. The situation was dicey and complicated, and he wore himself out trying to solve it. He ended up feeling paralysed and fragmented. A decision needed to be made and the status quo upset before things could move forward. He felt the situation was done and no amount of fighting, complaining, or scheming would change it.

Accused of drinking too much to denounce him Geoffrey Bardon felt pretty wrecked and psychologically broke. After spending a couple of days lying down he realised the situation was beyond repair and the best thing he could do was leave. He had to go. Time to close the book, pull the swords out of his back, recover and move on. He took his valuables, that being his radio, coat, and boning knife and swapped them for paintings. He bought some paintings and loaded up his van and drove out of Papunya in a rage.

Geoffrey Bardon was so angry. He was so upset. He was so very sick. He had suffered a nervous breakdown and back in Sydney he was admitted to the notorious Chelmsford Private Hospital in Pennant Hills for Deep Sleep Therapy. His treatment included some electro-convulsive therapy which left him with permanent damage. Physically incapacitated for the rest of his life.

A truth then, and now, is that within the ‘Aboriginal Race’ administration authorities an attitude is snuggled to ensure that the Australian local native genealogy is amplified as a living museum artifact and not part of a natural developing world.

An attitude designed to exploit history and resist any kind of substantive positive and lasting change for a certain selection of the Australian population. There is no desire for Australian mixed genealogy to be considered as mainstream humanness like English or European or Asian or African.

To pretend colonizers tried to make the ‘Aboriginal Race’ extinct by breeding them out goes against the grain of natural human copulation and reproduction.

No one pure thoroughbred of human species lives on planet earth.

Race is a social construct not a biological fact.

First nations people of the ‘Aboriginal Race’ today are not the same genealogy as “those who arrived here first” as no one knows who did arrive here first and from where they came from or what they looked like, or if they stayed or died out.

Proud to be a born and breed ‘Aussie’ just the same as all other born and breed Australians, warts, and all.

So Jedda, and Ngarra, what is your disability under the social model of disability? We are part of the ‘Aboriginal Race’ sir!