Behind the veil Albert Namatjira spirit is restless Part 1 of 3

Albert Namatjira was an Australian man who loved his country. At birth his parents named him Elea.

In the eyes of his kinsmen Albert was the ‘fruitful native hunter’. On his reappearance at camp he had to share everything he had procured not only with his immediate family, but with all those who had traditional claims upon his labours as dictated by the elders. This was his kinsmen, any blood relation or those who had ancestor connections. Co-operation and food sharing of this command were seen to be essentially required for the survival of the mob. A throwback to life lived in Australia 114 years before he was born.

The traditional belief was that Albert was expected to share everything and personally own nothing. Everything belonged to the mob collectively.

Over three blogs I am reviewing objectively the life and the messages of a very well loved and respected Australian man, Albert Namatjira whose physical presence of blood and bone are retained in the red earth while his soul’s spirit soars free.

His personal contribution provides his country, Australia, with a wealth of historical knowledge about what mistakes have been made in the past and how those same mistakes still, within a louder echo chamber, are occurring today.

As a man of great integrity Albert wants those who can influence genuine change to be aware and bring to the surface subconscious thoughts that connect him to created unwelcome actions.

Albert thought his fame as a painter would help the assimilation of his people among the whitefella and said it was “a good thing. Yeah.” in a press interview in 1958.

Albert was a Homo sapiens who lived on a Christian mission and retained a nomadic lifestyle where he moved around his local terrain in search of waterholes. A place where he camped in the open, and lived off the land respecting and grateful for all God provided him with.

The European whitefella had officially lived on the same continental land mass for one hundred and fourteen years when blackfella Albert Namatjira was born in his country, Australia.

Albert’s skills in whitefella watercolour painting have been implied as evidence of the potential success of blackfella absorption policies. Albert had many other skills and abilities that he embraced and used in his daily life as the situation required. Painting was not all he offered in an emerging society.

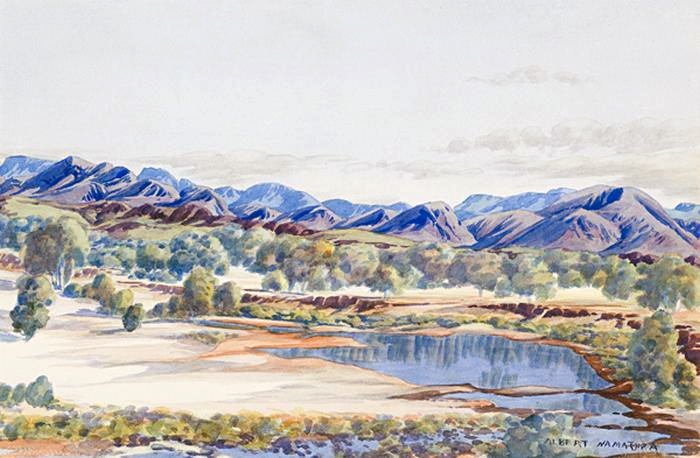

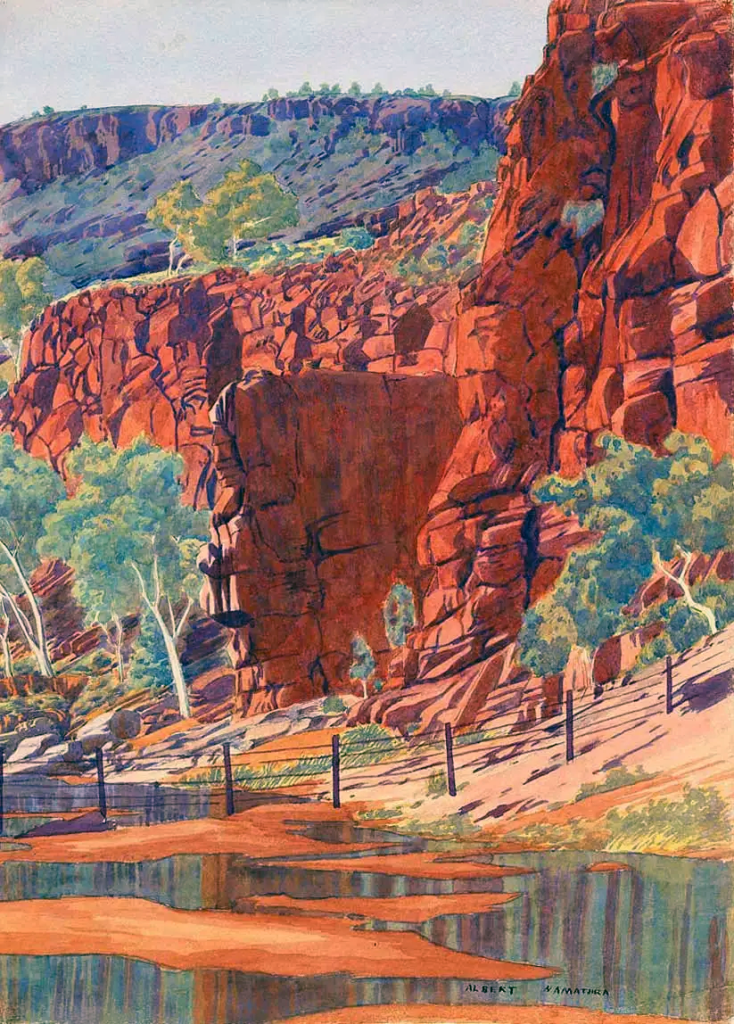

Albert was always happy spending time in the peace of his natural world. Arrernte terrain is rich with mountain ranges, waterholes, and gorges, which generate a diversity of natural habitats. He was a great walker, his high sensitivity allowed his human spirit to sour high as he roamed free from the restrictions of tribal, and government of the day laws involuntarily placed upon him, and which made his head spin.

In Albert’s home turf water is the source of life. The climate is temperamental with short periods of intense rainfall followed by periods of drought that could persist many years. An environment beleaguered, a rendezvous of continual survival, recovery, and golden years of prosperity. Australia.

Albert Namatjira experienced family life as a son, a brother, a husband, a father, an uncle, a grandfather, and an Arrernte tribal elder. Albert was most happy in the company of his family’s mob and some members of still living wild mobs who could not speak English and with whom he would hunt wild game. He lived life on the land as a man of the land.

Albert Namatjira’s story is portrayed as a tragic one: I see it as a confused story of inclusion. Without his connection and desire for what Western Society freely allowed him to do we would not have Albert’s story to share or his artwork legacy. Most of the restraint he endured was because of his desire to retain some of his ‘aboriginality’. Much the same as many other immigrants from around the world who have come to to our multi ethnic Australia who wish to retain some of their claimed genealogical background.

Albert’s parents allowed him to walk away from the old native way of life to nourish a dream of who he wished to become. For as long as he could, Albert protected his dream and plan for his life from unwanted influences, outside drama, and gossip.

Society during Albert’s entire life displayed an overall desire to protect people of his ‘Aboriginal Race’ genealogy’s welfare, as it was thought and evidenced, local natives could be powerless in fending and protecting themselves from living the old native way in an emerging, far from perfect, civilized society.

More than a century after the birth of the Commonwealth of Australia as one nation of people we find, in 2023, there is a magnitude of evidence that reinforces the old, worn to death, societal desire to protect the powerless ‘Aboriginal Race’ is alive and well.

Albert’s ‘aboriginality’ harboured important parts but not all of his personal identity. He liked to make things and could display control freak tenacity wanting things done his way. His inner strength came from not worrying about the ‘bullshit’. He mostly kept his thoughts, intentions, and ideas to himself to avoid becoming the centre of scrutiny. Albert’s moral conscience reflected time and time again he valued Christian beliefs. Revenge and payback where not part of his belief system.

Nor was ‘bone pointing’ something he tolerated as he thought ‘bone pointing business’ a was cruel nonsense.

Albert was proud of his local native heritage and was a member of whitefella society. Albert was never asked to give up being a blackfella. The local language, customs and traditions were his to keep or reject as he felt inclined. Albert had been taught English at school notwithstanding he retained a deep love for his mother tongue and also spoke, Aranda.

Some say Albert walked between two worlds, but he did not. He walked in a world of his own making. He made every day personal choices as all those living in Australia at that time did. Some choices proved to be lucrative and liberating, yet others more so later in life, caused him to be imprisoned and led him to lose his will to continue to paint or to live in this world anymore.

It was not what the whitefella gave Albert, more exactly, it was what the blackfella took from him that made him lose his will to paint and live in this world anymore.

Albert lived a complex life in a challenging period of Australia’s development. It was not easy for people like Albert to live with the Topsy-turvy whitefella and blackfella rules of that time. One boot in stride vocalised he was born a British Subject, the same as all other people born in Australia at that time. Yet, his other boot crooned the Northern Territory welfare song bogging the first boot down before it could step onto a level path.

Aranda refers to a local native language group. In their hunting and gathering days the Aranda, like all local natives for an unknown time before, had a rather basic tool kit, made up of mainly of spears, spear throwers, carrying trays, grinding stones, and digging sticks. The Aranda male youths after passing through painful body maiming initiation rites were able to achieve the full social status of an initiated blackfella.

Only initiated men were allowed to marry and to be hosted into the native spiritual world of local myth and sacred tradition. It was normal for girls to be married soon after puberty and be subjected to the wills of their husbands and to the older women of their husband’s family group.

Aranda country is located 125 kilometres west southwest of Alice Springs. From British settlement in 1836 it was ruled by the South Australian Government until 1911 when the Northern Territory was formed.

Albert’s father was born near Ormiston George of the Piltharra skin group, and his mother was born near Palm Valley of the Mpitjana skin group.

In around 1901, his parents meet when they came from Ormiston George and Palm Valley to the German Lutheran Mission seeking food and water during a time of severe drought. Albert’s mother was a woman forbidden to his father on the grounds of their traditional kinship mismatch – but they married anyway. His father was later speared in the leg and then forgiven for breaking the skin group tribal law.

Albert was born on 28 July 1902, in the desert Aranda terrain at the Hermannsburg Mission on the banks of the Finke River, Central Australia. A place of red desert soil, stunted trees, spinifex, rugged mountains, deep gorges, and arid plains. Albert was the first-born son of Namatjirritja (Jonathan) and Ljukuta (Emilie) who were members of Western Arrernte local native tribes.

Albert was his mother’s second child. He had an elder half-sister Clara born in 1898. Clara’s father was a German goat herder and skilled horse breaker named Pfitzner. Clara was a half caste.

Albert also had two same parent siblings, a sister Meta, born in 1906 who died in 1912 and a brother Hermann born in 1909 who also died during another prolonged drought and famine that afflicted Hermannsburg in the mid to late 1920s. Drought is a vast and extraordinary hazard of desert life. Many adults and 85% of local native children died during this severe natural weather cycle drought.

Elea was Albert’s birth totem name. Albert was his Christian baptism name. Namatjira was an inherited (flying ant) totem from his father which eventually was the family surname he used as an emerging watercolour artist. Albert due to his parents skin mismatch became of the Knguarea skin group. Knguarea became his kinship name.

In 1905, his parents, Albert and his younger brother were baptised in the Christian faith while still living at the Hermannsburg Lutheran Mission at the base of Mount Hermannsburg on the banks of the Finke River.

Very little is confirmed of Albert’s early life. He lived at the Christian mission attending the school and living in a dormitory, separated from his parents until he was 13 years old. He was described at the mission as quiet, a quick learner, intelligent, self-assured, and a thoughtful child.

During his life Albert freely moved in and out of western society.

From time to time a young Albert went walkabout with his relatives and other members of his mob to the bush. At age thirteen he stayed in the bush for six months for his initiation into manhood and exposure to local traditional culture and strict timeless, unwritten secret laws of the Arrernte tribe. He later became a tribal elder and while he did not practice secret and sacred ceremonies, he did live with the basic hunter gatherer indoctrination of sharing his wealth and belongings with all his tribal kin. Just like the ‘fruitful native hunter’ the tribe had hunter-gatherer claims on his wealth.

Through living at the Christian creed mission, he was able to read and write the national Australian language, English, as well as his local native tongue. As a boy Albert sketched scenes and events around him. The mission authorities encouraged him to produce carved and painted artifacts. He painted on coat hangers, bean-wood panels and made wall plaques, boomerangs, and woomeras. His imagery included tjuringa designs, biblical themes, and figurative subjects. He developed leather-work, carpentry, blacksmith, cameleer, and stockman skills at the mission where he worked for rations and then on neighbouring stations he worked for wages.

To avoid tribal and missionary controls, at 18, Albert eloped with Rubina (Ilkalita 1903-1974) and lived for three years in neutral country away from Aranda and missionary boundaries. Like his mother, Rubina was considered to be of the wrong ‘skin group’ for marriage and as such Albert violated the local native law by marrying outside the cultural kinship system.

His mob ostracized Albert for violating tribal law in marrying Rubina. During this periods away from the mission Albert found work on cattle stations and as a cameleer carrying goods to remote stations.

Albert was very kind to animals.

As a cameleer he travelled extensively throughout Central Australia and around the MacDonnell Ranges, the country he would later paint, the dreamtime places of his Arrernte kinsmen.

The spectacular scenery of Central Australia had become a symbol of Australian consciousness and national identity. On their second trip to the Hermannsburg mission in 1934, whitefella Melbourne artists, Rex Batterbee and John Gardner showed the local native audience their watercolour paintings. The locals were familiar with drawings of biblical scenes but viewing landscapes showing their own local terrains was a brand-new experience for them.

Albert wanted to emulate the watercolour artwork and asked for and was given his own box of watercolours and watercolour paper by the Mission Superintendent. In 1935 he painted his first watercolour which in 1949 he gave the title of ‘The Fleeing Kangaroo’ and signed.

In 1936, expressing an interest in learning to paint this Western way Albert volunteered to be cameleer, cook, and guide for Rex Batterbee travelling for two months in and around the MacDonnell Ranges. In exchange, Rex taught Albert how to draw, to use crayons and then to paint using watercolours. Blackfella and whitefella freely bonding as lifetime friends. Two years later while on another exhibition together Rex taught Albert photography.

In his unique way Albert blended his own connection to the structure of the barren desert with the rendering of rugged rocks and reflections in the water, the individualism of every tree and flower with contrasting colours to magnify illumination in nature’s true beauty. He is the first known Australian native artist to paint in the Western watercolour style and exhibit his original artwork professionally. Exhibitions that were a sell out in many whitefella cities.

Albert was included in the imperfect world of both blackfella and whitefella lived experiences. As was Rex Batterbee. Success brought Albert whitefella money, but with fame came hullabaloo. Under welfare ordinance he was able to and did buy, own, and sell property and freely withdraw his money from his bank account held in trust.

During their marriage Albert and Rubina had ten children. Five sons and five daughters. Some were born at the mission others were born when the family were on walkabout. Eight survived infancy. Sons, Enos (1920-1966), Oscar (1922-1991), Ewald (1930-1984), Keith (1937-1977), and Maurice (1939-1979)—and three daughters—Maisie (1923-1974), Hazel (1924-1949), and Martha (1929-1950). Their daughter Nelda (1928-1929) died at 17 months of age, and Violet (1938) their eighth child died at five months of age.

In 1944 Albert was included in Who’s Who in Australia.

With Albert’s involvement a film titled ‘Namatjira, the painter’ was made in 1946 and released in commercial cinemas throughout Australia in 1947. Many years after Albert’s death the film was re-edited in 1974 and this altered version is what one can watch today.

Around the age of 45 years Albert weight had ballooned to 18 stone (114 kilos) and he was diagnosed with having Angina pectoralis. His doctor suggested he lose weight, so he took his wife and family on a walkabout and enjoyed living off the bush and came back looking slimmer, fit, and healthy.

Albert was awarded Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation medal in 1953. He was presented to the Queen in Canberra in 1954 and elected an honorary member of the Royal Art Society of New South Wales in 1955.

In spite of his whitefella income generating capacity and the wealth that created for Albert he was expected by his blackfella culture to share everything he owned with his extended native kin. As his wealth grew so did his extended kin. He bought lavish presents for others. Various reporting indicates that at one time he was solo providing financial support for six hundred of his blackfella kin. As a direct result, he lived in relative poverty.

Continue reading in Part 2 Albert Namatjira’s Speak the truth, strip beliefs back to the core.