Albert Namatjira – Speak the truth, strip beliefs back to the core Part 2 of 3

Dreamtime is the foundation of the Australian natives creed, traditions, and culture. A belief that the ancestors made the entire world in a continuum of everywhen – the past, present, and future. The Rainbow-Serpent, a whitefella coined term, divulges myths known by numerous Australian native names. The myths all seem to signify a common deity who is the giver of life and creator of the natural landscape usually through its association with water.

The Rainbow Serpent is seen to be of immense proportions and inhabits deep permanent waterholes. A rainbow seen in the sky is said to be the Rainbow Serpent moving from one waterhole to another and the celestial theory that explained why some waterholes never dry up when drought strikes. When angry and in times of rage the Rainbow Serpent will cause storms and floods to act as punishment against those who disobey the tribal laws.

Albert Namatjira retained a deep understanding of the mythology of the Aranda and relayed the stories to others. He was a man who always adhered religiously to one ancient hunter gatherer tradition of sharing all food and possessions with his kin. He believed that the spiritual inheritance of the land was one big celebration encompassed in the dreaming that had been there for all of time.

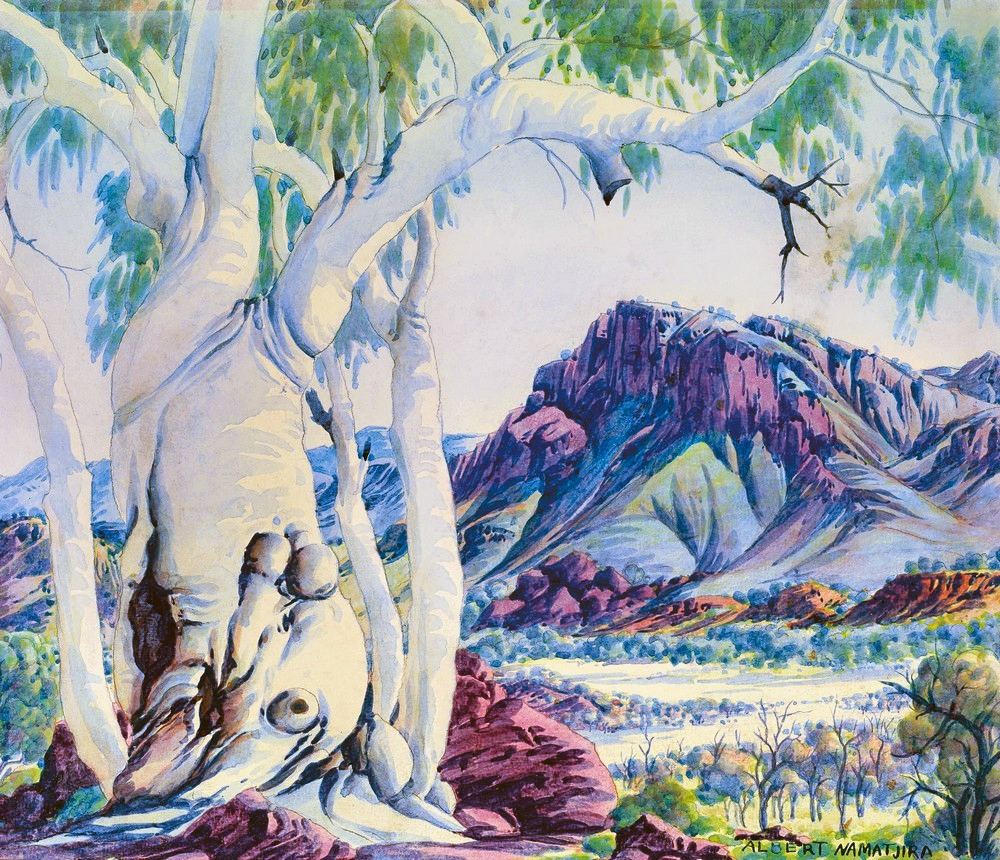

The impact on Albert in seeing Rex Battarbee’s paintings was instant and enduring as it gave him a reflexion of his own country that he had not seen before. An eye-opener to visual beauty, colour, light, and atmosphere stimulating a desire within him to capture what he saw using the whitefella watercolour.

Before Rex Battarbee’s intervention Albert had only seen his country in terms of its spiritual mythology and as a source of economic survival now he saw all that ever was and all that ever will be caught in a way that heals souls, hearts, and minds.

Albert was an incredibly respected, well known, loved, and honoured watercolour artist, who as far is known, had pure Australian native genealogy. Whatever ‘pure Australian native genealogy’ really is… full blood as a topic is a mindblowing labyrinth of free thought.

Albert’s mateship with war damaged ex-soldier and painter of whitefella genealogy, Rex Battarbee verified where one was born, or the colour of one’s skin has nothing to do with being included. Both men mutually learned from one another and formed a long-term relationship based on honesty, respect, and love, demolishing dividing cultural lines in the process.

All who new Albert commented on his distinctive dignity outwardly displayed for all to see. Albert, for most of his life, was known as a kind and loving family man, intelligent, resilient, determined, creative, stubborn, and self-directed. A hard worker with tenacity.

Albert’s legacy has been the target of forceful debate, twisting the artist into a figurehead of Australia’s ‘culture wars’. Instead of recognising the positive relationship he had with his Central Australian lifestyle and fellow settlers some commentators spout that his late in life fall from grace was inevitable and just a matter of time as he wandered between two worlds. His paintings are alive with a realisation that the naked human spirit is seen all around our natural environment. Take off the mask, drop the disguise, strong foundations help you soar. He became the creator of his artistic vision.

The power of the old tribal ways had come to an end for him. As a matter of survival Albert felt a need to carry on in some of the old set ways but it created a state of emptiness, weakness and fear inside him. Whether a blackfella or whitefella being alone in nature for days at a time is a powerful rite that allows encounters with spirit guides, ancestors and healing visions. Albert was his authentic self, he understood what his painting were capable of and saw his physical and spiritual place on mother earth.

Albert was a natural high achiever who had an innate connection to the spirit world. Throughout his life he spent months at a time nomadic in the countryside of his birthplace. Like a bumble bee travelling from flower to flower he developed an intimate compassion and sensitivity that gave him an ability to see and paint nature in a way that touched the soul, mind, and heart of others. The love he felt for the terrain he lived in allowed him to share the harshness of climate, the severity and lushness of the landscape, the exquisiteness, and vibrant colours of our illuminating natural and spiritual environment. His truth encaptured by the emotions that guided the brush in his hand.

In the “Daily News” newspaper article 14 May 1951, Albert Namatjira was quoted as saying “I paid more than £400- income tax last year to the Commonwealth Government but that same Government prevents me from building my own home on my own land with my own money.” It was reported that “Namatjira had hoped to build a ‘white man’s house’ as a retreat from his tribal worries. Last year Namatjira paid £400 in taxes to the very government which denies him citizenship rights.”

In the “Northern Standard” newspaper article 25 May 1951 it was reported that “Albert may not be able to continue his painting as he is so upset about the refusal of the Menzies Government (through Administrator Driver) to build his own home with his own money.”

In 1947, Albert was given his first income tax assessment. He did not comprehend how this could be possible. As an ‘Aboriginal Race’ person, he was a ward of the Northern Territory and he erroneously believed he was not a citizen of the Commonwealth who had to abide by the taxation laws that applied to whitefellas all around Australia. He could not understand why he was expected to pay income tax.

1949 through to 1950 life presented Albert with much personal tragedy. Albert travelled to Darwin where he viewed the ocean for the first time. When he returned to home to Hermannsburg, he sold the cottage he had built, and bought an Army disposals hut which he erected near the Mission buildings. In 1951 he moved to a camp at a waterhole at Morris Soak, several kilometres outside of Alice Springs. He lived in a crude hut built of bags and old iron.

In 1954 he flew to Darwin, Sydney, Canberra, then back to Sydney. He then travelled by train onto Melbourne then Adelaide and back to Alice Springs. The next year he spent much time on walkabout around the country he loved and painting trips.

In 1956 his much-loved father died. AMPOL petroleum gave him a new pickup truck with his name painted on the doors and he travelled back to Sydney with his son Kevin to collect it and drive the vehicle home. The next year he travelled to Perth.

In 1957 and 1958 Albert had two bouts in hospital after having a badly burnt foot and a severe injury to his left hand brought about by a bone pointing argument with Mudaka. People noted Albert looked sullen, aged, and ill. Five weeks after leaving hospital the second time Albert went on a five-week painting excursion and then returned to live at the camp at Morris Soak.

Late in Albert’s life, the conflict between Federal, Northern Territory, and tribal law resulted in Albert being sentenced to six months and imprisoned for two months. Bureaucracy and exploitation were the big trouble he felt that let him down.

Under the Welfare Ordinance Act the control and welfare of Australians with pure native genealogy in the Northern Territory belonged to the office of the Chief Protector of Aborigines who in good faith thought it was best that people of the ‘Aboriginal Race’ would be better off if they did not consume alcohol.

One notes that in current times the same ‘dry’ protection policy exists for ‘Aboriginal Race’ communities in many parts of Australia. While it has been reported that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are less likely to drink alcohol than other Australians those that do drink are more likely than other Australians to drink at dangerous levels, both over a lifetime and on a single occasion and to also attend hospital for alcohol-related conditions such as liver disease.

After Albert obtained bureaucratic ‘on paper’ no conditions Australian citizenship he displayed an unhealthy fondness for the ‘demon drink’ alcohol. Bureaucratic ‘on paper’ citizenship gave him the legal right to go for a drink to a pub and to drink at home.

This was the same legal right of any whitefella or part ‘Aboriginal Race’ person, such as his half-sister enjoyed. He had the right to vote in elections, to drink at hotels, to take alcohol home, to build a house anywhere where a whitefella could, and demand payment of the basic wage if he was formally employed. However, the downside was his children were still considered wards of the State and therefore if he built a house in Alice Springs, his children could not legally stay with him overnight nor was he able to without permission freely roam local native reserves anymore.

Albert’s heart felt big trouble was coming and he did not know how to stop it.

Albert quickly became openly addicted to liquor. Some say Albert was a confirmed alcoholic.

Morris Soak was a secluded place in the hills a few miles west of Alice Springs and is where Albert chose to live in the years leading up to his imprisonment. Paid for by Albert liquor of all kinds was delivered by taxi to his camp. Wine by the flagon, spirits by the bottle were consumed by the diverse crew. Drunken brawls and orgies became a common scene among hangers-on at his camp.

Considering the safety of all concerned the authorities became resolved to put a stop to the hazardous, often violent, drunken orgies at Morris Soak.

In 1958 at one such drunken orgy, a local native woman who was pregnant was killed allegedly by her intoxicated local native husband. Albert was told that liquor was the indirect cause of the woman’s death and supplying liquor to members of his tribe who were wards of the State was his sin.

“The defendant who is the applicant was charged with having committed an offence on 26th August 1958 near Hermansberg in the Northern Territory of Australia. The offence charged was that he did supply liquor to one Henoch Raberaba, a person who is a ward within the meaning of the Welfare Ordinance 1953-1957, contrary to s. 141 of the Licensing Ordinance 1939-1957.”

A murder that Albert was not directly involved in occurred and he was charged with supplying alcohol to members of the ‘Aboriginal Race’ community at his camp at Morris Soak. This provision of alcohol to full blood wards of the Northern Territory natives was an illegal act at the time. As the illegal supplier of the intoxicating liquor, Albert was morally implicated in the murder. The murder was not pursued or charged with any offence or crime.

Albert was sentenced to six months imprisonment with hard labour. A public outcry, two court appeals saw the sentence reduced to three months. Albert served two months of ‘open’ detention at the Papunya settlement in March-May 1959.

There was no public outcry against the unjust law itself only how it persecuted the famous naive Albert.

After serving his two months Albert was released from the Papunya Native Reserve, looking as if he had lost his will to live in this world anymore. He was in a state of severe depression and his interest in painting had vanished. He accepted the offer of a small cottage at Papunya, but his health condition rapidly deteriorated. He was admitted to the Alice Springs Hospital when he suffered a heart attack, and with the onset of pneumonia it was only a matter of hours before he died.

Albert lived for 57 years spending most of his final months at the Hermannsburg Mission station at the base of Mount Hermannsburg on the banks of the Finke River in Central Australia. A place he began his life. A place he became reconciled to his loved Christian mission, his wife, relatives, and friends. A place he left his physical body behind due to hypertensive heart failure complicated by pneumonia.

As a ‘full blood Aborigine’ under Northern Territory law Albert Namatjira was never technically precluded from bettering himself. Albert had self-imposed limitations by his lifelong regard for traditional tribal law which compelled him to share ‘all’ of his belonging with all his tribal relatives. Mother Teresa, a Christian saint, displayed the same moral value. As an elder of his Arrernte mob sharing was the main tribal tradition he engaged with. His children were baptised Christians and were not indoctrinated with the strict secret tribal laws of his parents mobs as he had been.

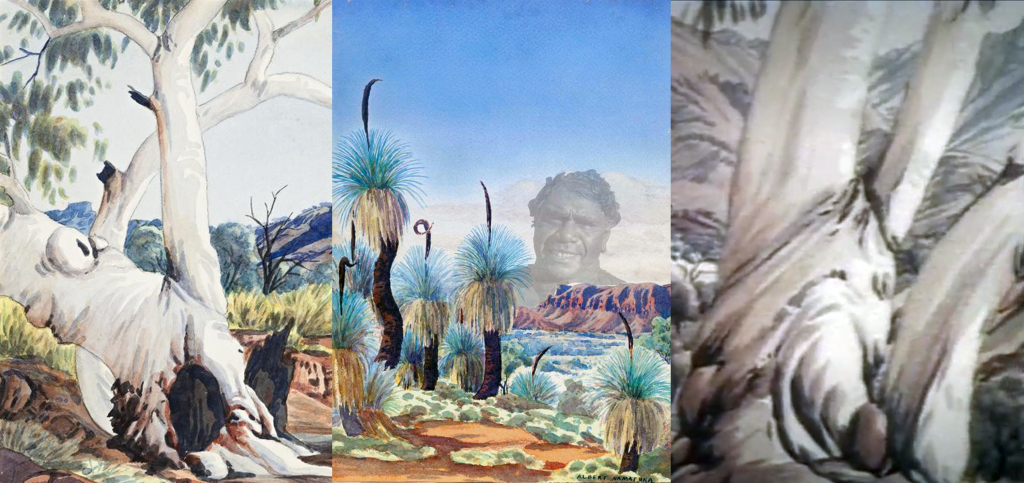

Albert was a ‘full blood’ local native that painted around two thousand paintings. Exceptional heart of Australia landscapes, fauna, and flora, with ghost gums that fill his frame have been immortalised in the paintings that the artist ‘Albert Namatjira’ created. Albert’s use of powerful reds, ochres and purples made his landscapes come alive. Landscapes that activated his physical and spiritual connect and love of our country, Australia.

Behind the veil, Albert’s spirit is restless because his story is not being told with truth. His name and life circumstance have been turned into a labyrinth of myth and legend of the dreamtime and are being used to create a public outcry of division obsessing sympathy to allow a continuance of his name and legacy to be used in inappropriate ways.

Calculating the copyright term for a given work can be complicated because copyright legislation has changed over time. When Albert Namatjira died his copyright lasted for 50 years from the date of his death. In 2005 copyright legislation changed the time frame from 50 to 70 years, increasing Albert’s copyright extinguish date by 20 years. Variations from these general rules may apply to some of his artwork.

In 1957 Namatjira signed a legal agreement with publishing company Legend Press. This contract stated that Legend Press would pay royalties to Namatjira in exchange for receiving the sole right to reproduce all of his paintings. In return for this licence, Namatjira was to receive an ongoing economic benefit through royalties or licence fees. He kept ownership of the copyright of his artwork.

When Albert died in 1959 his will left his entire estate to his wife Rubina. The Public Trustee for the Northern Territory Government was responsible for administering the will and his estate.

Rubina died in 1974 and the Public Trustee continued to manage the remaining 35-year copyright on behalf of her estate. In 1983, the Public Trustee decided to sell the remaining 26-year copyright to his artwork for $8,500 to John Brackenberg of Legend Press without consulting the family. The value or purchasing power of $8,500 in 1985 translates to $33,813- in 2023 value. There is no evidence to say that the original sale by the Public Trustee in 1983 was unreasonable or a reckless giveaway of something with a much greater value.

The returning of Albert Namatjira’s art copyright to his descendants in 2010 involved Australian philanthropist and businessman Dick Smith, acting as a mediator on their behalf in which Dick Smith convinced Legend Press owner’s son Philip to agree to their buyback of the art copyright for the symbolic sum of one dollar. This auspicious conclusion is referred to as divine intervention, with both men and Big hART arts lobbying organisation, appearing altruistic in their roles as benefactor and ‘white saviours’.

Dick Smith, ‘white saviour’ then donated $250,000 to the Namatjira Legacy Trust.

Once again Albert Namatjira was the fruitful hunter but this time he had to share everything he had procured not only with his family, but with all those who had traditional claims upon his labours as dictated by the ‘white saviours’.

Albert Namatjira’s art may be museum artefact but he personally was not.

It is just plain wrong for the ‘Aboriginal Race’ to be treated as a museum artefact to be preserved outside of human being natural order of life.

Throughout his life Albert demonstrated his mastery in taking the reins and moving towards achieving his ambitions. He understood everything he experienced played a part in getting him to the next level of his journey, but he did not know how to integrate what he loved about the blackfella lifestyle into what he desired from the whitefella lifestyle. Because of nonsense whitefella pointing the bone laws he found himself at the crossroad of facing a simple yet not easy decision time and time again. Did he take the leap? And what then did that mean? What might be possible if he was brave enough to take the leap?

What emotional and mental baggage would be released from moving forward with pure intentions to follow his passion without the conflict of blackfella vs. whitefella laws and myths?

Next Part 3 of 3 – Albert Namatjira is happy with what the whitefella gave but not with what the blackfella takes.